courtesy of Sonia Tapiarz courtesy of Sonia Tapiarz I learned this morning that someone drew two swastikas and the n-word on an East Penn school bus yesterday. A passing motorist took a photograph and alerted authorities. The school district issued a press release this afternoon, saying it "denounces and prohibits this type of racial harassment and is in the process of conducting a full investigation." Our district thus joins others in the area confronting such displays in recent weeks. Southern Lehigh High School has been host to a number of openly racist and homophobic slurs this school year, including students using the Hitler salute. At Saucon Valley, a white student posted a video of a black classmate eating chicken which he narrates using the n-word and series of racist stereotypes. These are a part of a much longer list of incidents that have been reported throughout the Lehigh Valley, both in and outside of schools. Racism and anti-Semitism, of course, are nothing new. Nor is graffiti such as that witnessed on the East Penn bus. But over the last year these kinds of public expressions have become more common. The FBI reports that hate crimes were up 6% last year, with African-Americans and Jews being the most frequent targets. Anti-Muslim hate crimes were up 67%, the greatest increase in fifteen years. Regardless of who drew the graffiti on the school bus window or what their motivations were, incidents like this represent a real danger to our community. Words matter. And these kinds of incidents should not be accepted as normal. The swastika and n-word represent-- very directly-- the anti-Semitism and racism that have characterized some of the darkest moments in our history. I have heard some say that we should ignore these kinds of incidents, either because they are petty, or to avoid giving the perpetrators the attention they seek. I agree with this approach in many cases, but not in this one. Sometimes silence is dangerous. The rise of the Nazi party in Germany in the 1930s was characterized by the appearance of similar (and also seemingly petty) graffiti. The n-word continues to be used today to incite violence against African-Americans, just as it was closely associated with lynching in the past. The need to confront, rather than ignore, this type of incident is particularly important in our district, where minority students represent only a small fraction of the population (4.2% are African-American) and are thus particularly vulnerable to racial and religious intimidation. So how can we use this incident to help our kids and our community do better? I'm no expert here, but I'll tell you what I'm going to do with my own kids: #1 Give them information: We might all be forgiven for wanting to shield our kids from the harsh and brutal truths behind these symbols. But I think kids need more information, not less. Kids lack much of the background and context needed to understand why such symbols are provocative or shocking or dangerous or scary. Simply telling them they are taboo is not enough; giving them knowledge helps both strip the symbols of their power and make sense of a complicated world. I'm going to explain to my kids the historical significance of these symbols, and what kinds of groups use them today. #2 Give them tools: I am going remind my kids that if you see something, say something. This is the phrase used by the Department of Homeland Security to encourage reporting evidence of terrorism. But the same idea applies in the far more common circumstance of witnessing acts of racism, anti-Semitism, or other forms of hate. I will remind my kids that saying something can be hard, because calling out such ugliness can be socially awkward and invite retaliation. But it is precisely the silence that allows a wrong to continue and grow. I’ll highlight for my kids the good example set by Sonia Tapiarz, the woman who reported the East Penn bus incident to authorities. She could have easily just shook her head in disgust and went about her day. But instead she took the time and effort to document what she saw and alert us. As a result of her saying something, positive change can perhaps now come out of the incident. #3 Give them empowerment: I am going to ask my kids about their opinion of the graffiti incident. I'm going to encourage them to ask lots of questions, and help them them find answers on their own. I want them to know that they should not stand by passively as events in their community unfold. I want them to a part of those events, bringing their own values, perspectives, knowledge and skills to the table. #4 Give them examples: I am going to tell them about the steps I am taking in response to this issue. Step one is sharing this post with the larger community. Step two is writing the East Penn Superintendent, Dr. Mike Schilder, directly. I am going to share with him my belief that students in our district will learn important lessons from how he leads the district in its response to this incident. I am going to remind him of his responsibility as the most visible educational leader in our community. And I'm going to ask him to use his expertise as both an educator and leader to teach our students about what swastikas and the n-word represent, how they can be dangerous, why incidents like this are happening now, and what concrete steps the district is taking to confront them. #5 Give them resources: I am going to ask my kids to find a community organization devoted to addressing the issues of racism and anti-Semitism to which we can make a donation of our time or money. They will see how our family can work with others to make such incidents less likely in the future. I want my kids to gain experience advocating for some of the core values that serve as the bedrock of our community-- chief among them the fundamental humanity and dignity of us all. We should not put our heads in the sand when it comes to issues like this, or dismiss the significant concerns they raise as just “political correctness.” As the conservative philosopher Edmund Burke famously said, "the only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing." I would add that evil doesn’t come all at once; it sneaks up on us, little by little, with many of those involved not even aware they are caught up in it.

8 Comments

I have been thinking a lot about the issues of school safety in recent weeks. I share some of my thoughts in a Morning Call editorial that was published today. Please check it out:

http://www.mcall.com/opinion/yourview/mc-school-safety-mesasures-munson-yv-0515-20160514-story.html  Don't Panic via photopin (license) Don't Panic via photopin (license) Classes resume Monday morning at Emmaus High School, after security concerns led to a lockdown and early dismissal on Thursday and cancelling of classes Friday. As our kids try to return to their normal routines, I urge all parents, students and staff to consider how much damage spreading unsubstantiated rumors about the incident last week can do:

As the unsubstantiated rumors of gangs and guns and knives and threats spread late last week, East Penn student Caleb Burkhardt posted his reaction to the issue that was more thoughtful and sensitive than anything I read by any adult: Today at Emmaus High School, there was a lockdown initiated at 8 AM due to a contraband search after a student dropped a box of bullets nearby/in one of the cafeterias. Now if you know me well, you'll know I despise being in the dark; but the proper response to being in the dark is not creating and or spreading rumors. It's human nature to panic, human nature to believe the first thing you hear. But just because it's the first thing you heard doesn't make it true. All that it has succeeded in doing is creating an unnecessary atmosphere of panic and fear. According to the district attorney, all that was found was the box of 50 .22 caliber bullets. That's it. I understand that many people do not trust law enforcement and the like, but when it comes to the safety of students and a town where the worst law enforcement has done is enforce 2 hour parking in the triangle, I'd trust what they say over the hearsay being spread by other students. Just because a majority claims it is true does not make it so. Now lets address some of the rumors. No guns were found, no one was arrested, there is no confirmed "gang." There were no knives or drugs found. The DA stated that the only thing found were the bullets. While there may be a gang or may have been/be a plan to shoot up the school, it remains unconfirmed and at this point is - as far as I am concerned - hearsay. That isn't to say that being worried and panicking was an incorrect response, by all means it was perfectly reasonable. But what was not reasonable was spreading unconfirmed statements that do nothing but further the chaos. I understand many of you do not want to go to school tomorrow, and understandably so. However if it is because you feel "unsafe," the school will have Emmaus Borough Police on campus, certainly able to stop any shooter. I've seen people say that yes it is true that there is going to be an attempt at a shooting tomorrow. Not to offend or call out these people, but unless your source is the person intending on shooting other people (in which case why haven't you reported it?) I am inclined to believe otherwise. There is a limit to better safe than sorry, and here we see it. Stop furthering the fear and chaos. Think before you post. The lockdown on Thursday was not a signal for us to panic about the safety of our high school. It was a signal that we have well-trained and prepared administrators doing their jobs. I don't know more than any other parent what our law enforcement professionals will ultimately learn about this incident; whether it was an accident, a hoax, or a real threat. But no matter where the truth ultimately lies, unsubstantiated rumors and panic WILL do harm and will NOT make our kids safer. I write this not only as a member of the school board, but also as a father whose daughter was in the high school Thursday morning. So I have a very personal understanding of the anxiety that this kind of incident can produce. I call on everyone in the community to resist letting this anxiety morph into rumor-filled hysteria. And in the spirit of lightening our collective anxiety, I end with Monty Python's classic take on a moral panic and the logic of the rumor mill in a much different time:  The East Penn School district administration has asked to hire a school resource officer (SRO) for Emmaus High School, at a total cost of approximately $100,000 annually. An SRO is a police officer who has additional training in working with juveniles and schools. To me there are three main questions that should be answered in order to form an educated opinion about this request:

Over this past week, I've written three different pieces in which I share what I learned myself in trying to answer each of these three questions. I did my best to find all of the research and data available on SROs, and evaluate this research both in terms of its quality and its relevance to the particular conditions we have here in our district. I outline the answers I discovered in the following posts: What I learned in a nutshell: Contrary to what we might assume by watching the news, our schools are very safe. Indeed, they are MORE safe today than they were ten and even twenty years ago. At Emmaus High School, the number of serious behavioral incidents are not going up; if anything, they are declining. At the same time, the (limited) data we have on the effectiveness of SROs shows that they can increase the PERCEPTION of safety, but do not increase the REAL safety of schools. So while we may all want to make our schools even safer than they are, an SRO is unlikely to do that. And finally, the research shows that SROs have the effect of criminalizing student behavior that is best handled by school officials rather than the police. Moreover, SROs can both undermine the authority of other school officials and expose the district to greater legal liability. All of this is true even if SROs are highly trained, well-intentioned, and carefully supervised. The Emmaus Police Department, Macungie Police Department and the State Police all do an excellent job already keeping our schools safe. The district administration has put a great deal of careful thought, time and effort into the SRO proposal. I appreciate the work they have done in developing it, and acknowledge the important experience many on the district’s leadership team have had with SROs in other districts. They have also reviewed many reports and studies, but have-- in my judgment-- relied on those that are of lower quality (relying on perceptions rather than objective data, for example) or that speak to less central questions (for example, the best way to develop an SRO contract) in advocating for the new position. My daughter will attend Emmaus High School next year. And so there is naturally a part of me that says YES-- put a police officer in every hallway! But I am committed to making evidence-based decisions for our district, and that kind of gut reaction doesn’t make for good public policy. Conditions in the district could change, or new research could emerge about the benefits of an SRO, that would lead me to reconsider. But right now, based on the evidence, I do not support hiring one for East Penn.  photo credit: Cuffs6 via photopin (license) photo credit: Cuffs6 via photopin (license) This is the third of three pieces I will post focusing on the issue of SROs. The first focused on the decreasing amount of violence in schools and the second on the data showing SROs do not make schools safer. I was a (casual) hunter when I was a kid, and I started when I was ten or eleven, hunting rabbits and squirrels with my father. One fall day during 5th grade school recess, I discovered that I had forgotten to take a small box of .22 caliber bullets from my jacket pocket after a day in the woods the previous weekend. My elementary-school mind thought I might impress some of my fellow students with the box, so I showed it to a few of my friends on the playground. One or more of them, rightly, let a teacher know and I was quickly brought to the principal’s office and made to understand the depth of my mistake. I never did anything like that again. As I’ve learned more about SRO programs in the schools, I’ve often wondered how different reactions today might be compared to the (effective) reaction my principal had 30+ years ago. Would I have been suspended from school? Arrested? Charged with “making terroristic threats”? Quite frankly, I don’t know. Previously, I wrote about the lack of evidence SROs improve school safety. Unfortunately, there is evidence they can actually be harmful. Having a police officer constantly in a school can have the effect of criminalizing student behavior, as it makes it more likely that offenses previously handled by school officials-- particularly those that are not serious-- become matters for the criminal justice system. My own childhood experience many years ago might, today, be one such example. An important study published in the Journal of Criminal Justice finds that such concerns are warranted. The research examined several dozen schools over a three year period, approximately half with SROs and the other half without them. Here is what the results show: “[T]he high number of disorderly conduct incidences at SRO schools compared to non-SRO schools was consistent with the belief that SROs contribute to criminalizing student behavior. Having an SRO at school significantly increased the rate of arrests for this charge by over 100 percent even when controlling for school poverty. Given that disorderly conduct was the most common charge in this study, these results have serious implications for schools, law enforcement agencies, and juvenile courts.” (p.285) Another study, published in Justice Quarterly and based on a national sample of several hundred schools, comes to a similar conclusion: “[A]s schools increase their use of police officers, the percentage of crimes involving non-serious violent offenses that are reported to law enforcement increases” (p.642).

And if I haven’t lost you yet in all the data, let me report on much more hand-on, qualitative research. University of Delaware criminologist Aaron Kupchik closely studied four schools in different places around the U.S.. He interviewed teachers, staff and students in the schools, and then spent months in each one, logging hundreds of hours trailing administrators, talking with students, and observing what happened in the hallways, cafeterias, parking lots, and classrooms. He found the SROs in the schools to be both approachable and professional. And teachers, staff and students all generally liked and respected them. Despite this, he also observed the criminalization of student behavior in action in his research, leading him to conclude “for all but the most violent areas, it is a bad idea to keep police in schools. The potential harms to students are serious and widespread.” This last study raises an important point: The potential problems with SROs do not stem simply from bad officers, or poor training. SRO programs may harm student wellbeing even in cases where school administrators have good rules for involving SROs and the SROs themselves are well-meaning and well-trained. The root of the problem is this: SROs contribute, often unwittingly, to the “school-to-prison pipeline” that is being driven, in no small part, by growing inequality and poverty in our schools (over half of all public school kids now live in poverty; over 20% in Emmaus High School). What this means is that even good SRO programs can cause problems. Beyond these harms to students, there are other potential risks too. Even if students all behave, there can be things to worry about. The presence of SROs can undermine the authority of administrators, thus having the paradoxical effect of lowering discipline in a school rather than raising it. The issue of legal liability for the actions of SROs in schools is another concern. This issue became more important to me after reading about the SRO who accidentally fired his gun inside a high school near Scranton. Luckily nobody was killed in the incident. But it underscores the fact that consideration of an SRO for our own high school should include not only whether we need such a position and whether such a position would be effective, but also the range of potential dangers that might come too. I haven’t been hunting in years now, but my childhood experience with playground boasting about a handful of bullets makes me mindful today that our approach to school safety can have unanticipated consequences. What the data show is that these unanticipated consequences are real and should be a part of the conversation.  photo credit: The law... via photopin (license) photo credit: The law... via photopin (license) This is the second of three pieces I will post this week focusing on the issue of SROs. The first focused on the myth of increasing school violence; schools are safer than they’ve been in decades. The East Penn School district administration has asked to hire a school resource officer (SRO) for Emmaus High School, at a total cost of approximately $100,000 annually. An SRO is a police officer who has additional training in working with juveniles and schools. I do not support hiring an SRO for the district right now, in part because the data shows that hiring an SRO does not achieve the goal of greater safety. The strongest arguments in favor of an SRO is that it makes a school safer. An SRO can be proactive, and thus might be able to deal with discipline issues before they get out of hand; they might serve as a deterrent to criminal activity on schools grounds; and they might help educate or even mentor students in ways that keep them out of trouble. The logic certainly makes sense, and I believe the administration is sincere in its belief that an SRO can help in these ways. The trouble is the research on the effectiveness of SROs in schools simply does not bear out these benefits. Research Results: There is “no evidence suggesting that SRO or other sworn law-enforcement officers contribute to school safety.” The most compelling data on this issue comes from a peer-reviewed publication by scholars at the University of Houston and the University of Maryland. They use data drawn over time from almost 500 schools around the country, some of which had police in the schools, others that didn’t, and still others that started with no police officers and then added them. They conducted statistical analysis of the data that allowed them to ask how effective SROs were in the schools, controlling for other factors such as the size of the school, the poverty rate in the school, and so forth. What did they find? There is “no evidence suggesting that SRO or other sworn law-enforcement officers contribute to school safety.” In other words, as much as we might want SROs to serve as a deterrent in schools, to be proactive in preventing crime, and decrease violence through mentoring and education, they have not had this effect in the hundreds of schools that have tried them. An internet search will certainly turn up reports claiming SROs in schools are effective, thus contradicting this research finding. But if you actually read such reports, you find that “effective” is defined in such claims merely as “popular, as measured by opinion surveys.” This pattern led the U.S. Department of Justice report to conclude in 2010, and the Congressional Research Service to repeat in 2013, that “studies that report positive results from SRO programs rely on participants’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the program rather than on objective evidence.” Pennsylvania Report: There are “no notable differences” in either violence and weapons incidents, or in truancy rates, between PA schools that hired SROs and comparable schools that did not. A good example of this is the PA Commission on Crime & Delinquency’s 2005 evaluation of SROs in Pennsylvania schools, including several schools in the Lehigh Valley. If you were to read just the report summary, you would learn that support for SROs is “strong” and that they are “effective” in reducing the incidences of crime. But the body of the report makes clear that these conclusions are based solely on surveys of what school officials perceive to be happening, not actual evidence of a real decline in criminal incidents. Moreover, buried in the middle of the report (pp.68-69) is analysis of hard data on student behavior that is not even mentioned in the summary. This analysis took each Pennsylvania school with an SRO in the study and compared it to three other schools that were similar in terms of location, student characteristics, and so forth to see if the schools with SRO officers lowered their rates of crime or truancy. Contrary to the findings of the opinion surveys, the report found there are “no notable differences” in either violence and weapons incidents, or in truancy rates, between PA schools that hired SROs and the comparable schools that did not.

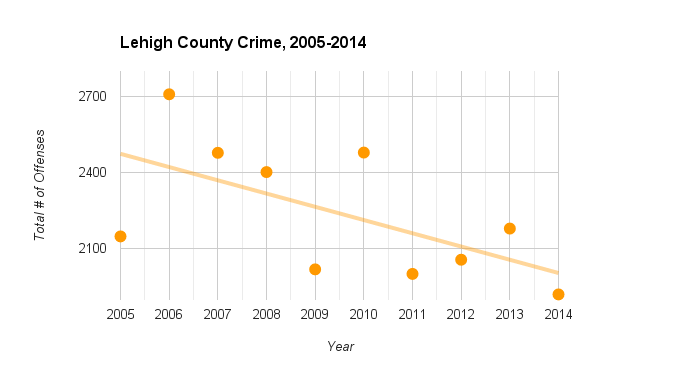

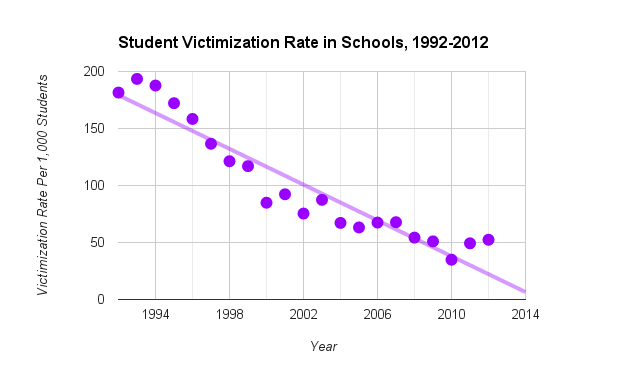

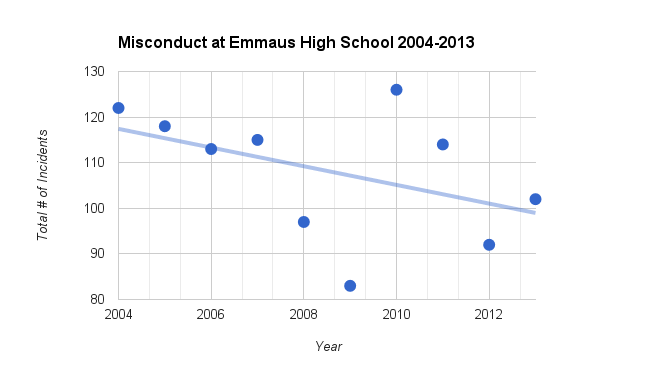

To summarize: Existing research shows that SROs in schools increase the perception of safety, but do not increase the actual safety of schools. There is certainly lots of room for additional research on this topic. I did an exhaustive search for high quality studies and was frankly surprised how little had been done, given the importance of these programs and the level of taxpayer funding they now command. More research is needed, but the best available data to date suggests that hiring an SRO officer will not increase safety at Emmaus High School. None of this data suggests that local and state police departments aren’t important to school safety. In our own district, police departments have good working relationships with district officials and assist the schools when there are problems. I hope that continues! What the data does show is that schools themselves should not get into the policing business. I acknowledge that the lack of conclusive research means reasonable people may disagree on this issue. And I respect that many people have had good experiences with SROs and good reasons for wanting one for the district. The issue of school safety is very personal to me too; my daughter will attend the high school next year. I therefore can’t help thinking about SROs not just as a school board member, but as a father. But the desire to keep our kids safe shouldn’t blind us to facts, and the best research-based evidence we have right now makes it difficult to justify hiring an SRO. The data show that such a hire will not accomplish the goal we all share: making schools safer. Tomorrow’s post: While objective data suggests SROs do not make schools safer, there is some evidence that they can cause a number of harms, even when officers are highly trained and excellent at their jobs. I will address this issue in my post tomorrow.  photo credit: sombras con lagrimas adentro via photopin (license) photo credit: sombras con lagrimas adentro via photopin (license) This is the first of three pieces I will post over the next three days focusing on the issue of SROs. The East Penn School district administration has asked to hire a school resource officer (SRO) for Emmaus High School, at a total cost of approximately $100,000 annually. An SRO is a police officer who has additional training in working with juveniles and schools. I do not support hiring an SRO for the district right now, in part because the perceived need for one rests on a myth about public-- and school-- safety. Let me explain. Newspapers, television and radio all offer us a constant drumbeat of threats to our safety. The news is often little more than a catalog of murders, assaults, robberies, and other crimes happening around us. Social media like Facebook and Twitter support this drumbeat by letting us all “share” stories of the dangers of the modern world. Those of us that closely follow the news can therefore be forgiven for believing-- as half of all Americans do-- that violent crime has increased over the last two decades. But this is a myth. We are bombarded by news of crime because such stories sell papers, not because such incidents are on the rise. It simply isn’t true that crime and violence are increasing in our society. And much of the support for adding a police officer in the high school is predicated-- often implicitly-- on this false sense that our communities and schools are less safe today than when we were in school ourselves. Let’s look at the reality. Nationally, violent crime has dropped dramatically over the last two decades. Today, we are less than half as likely to be a victim of violent crime than we were two decades ago. And this national trend holds locally too. Last night I pulled the crime statistics for just Lehigh County from the Pennsylvania Uniform Crime Report System. What do they show? Last year crime was at its lowest level in at least a decade. (You can click on all the graphs below to see the underlying numbers; the lines on each graph are generated automatically to show the overall trends in the data). But what about schools? It is reasonable to ask whether our schools are becoming more dangerous even as our communities become safer. But this too is a myth. Schools are safer today than they’ve been in decades. Detailed information about school crime and safety from the National Center of Education Statistics shows that the chance of students being a victim of a crime in school is down more than 72% from its high in 1993. Wow! This is great news, of course, but what we really care about is our own schools right here in East Penn. Using data from the PA Department of Education’s Office of Safe Schools, I created the following graph showing the incidents of misconduct at Emmaus High School. The results show there has been no increase in misconduct over the last decade that might require a police officer’s assistance; the overall trend, in fact, is downward. The data on individual types of misconduct, such as assault, are similar. The administration has argued that adding an SRO to the high school is “essential in creating a safe environment.” I disagree, because the data on crime nationally, the data on crime in our own county, the data on the safety of schools nationally, and the data on the safety of our own Emmaus High School all point to the opposite conclusion. Much of the impetus for adding a police officer is rooted in a pervasive myth that our community, and our schools, are becoming less safe. It simply isn’t true.

None of this suggests that violence and crime have disappeared from schools entirely. As parents and as community members, we want to make our children as safe as possible. Therefore, it is worth asking whether an SRO would improve safety even further. Tomorrow, I will address this question directly. Unfortunately, the evidence shows that SROs are not effective in making schools safer. In addition to the many links above, I suggest the following if you are interested in learning more about crime and school safety:

|

Details

Categories

All

Archives

December 2017

|